Corporate America Is Almost Out of Pandemic Cash

It took two years for the Federal Reserve's rate hikes to kill the economy...

Back in 1947, the central bank started raising interest rates to combat rampant inflation. It wasn't the kind of inflation we suffered in the 1970s... This was driven by the post-war boom.

Soldiers came home from World War II with more cash than they knew what to do with. The national unemployment rate was under 2%. And manufacturing was shifting back to business as usual.

All of that caused demand for goods to spike while supply remained stagnant... driving inflation way higher.

The Fed's job was an odd one. It had to cool down the economy while most everyone – corporations and households alike – was flush with cash. Those liquid balance sheets meant it wasn't until 1949 that the Fed's actions officially tipped us into a recession. And it was a mild one at that.

It took at least 18 months for higher interest rates to finally eat away at so much extra cash. At that point, companies were no longer able to refinance.

We've talked a lot about how today's economy mirrors the 1940s post-war economy. And today, the next phase seems to be showing up...

Corporations built up their balance sheets during the pandemic. Most paused all unnecessary spending, just in case. Not only that, but the government flooded our economy with stimulus. So when the economy rebounded faster than expected, companies found themselves with more cash than ever before.

Back in April, we wrote that corporate balance sheets were finally returning to "normal"... down from historically rich levels. This month, things look a little different.

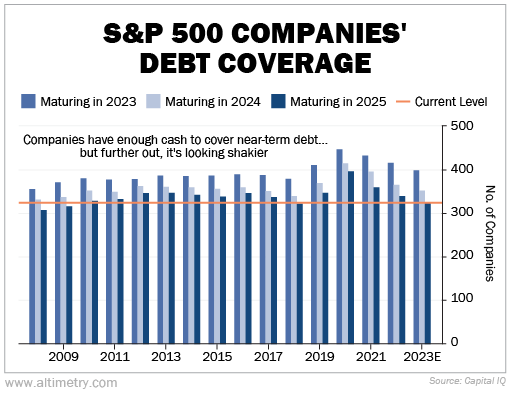

High interest rates are starting to take their toll on corporate balance sheets. You can see this in the chart below. It shows the number of companies in the S&P 500 with enough cash to handle debt coming due in the next three years.

As you can see, most companies still have enough cash to cover this year's debt. But when you look at all maturing debt through 2025, the picture isn't so bright...

Companies now have slightly more cash relative to maturing debt than they did in 2009... though it's a good deal lower than the average over the past 15 years. And that's a change from April, when companies had way more cash.

The more companies with enough cash to cover debt, the less risk there is in the market. Roughly the same number of companies had sufficient cash in 2018 as what we're seeing today. Any lower, and we're getting back to Great Recession territory.

Eventually, something has to give. Companies typically refinance their debt roughly one to two years out. So if they want to refinance this 2025 debt, they need to start soon.

We've been saying for a while that refinancing issues could surface somewhere between the end of 2023 and early 2024. This data only reaffirms our view.

Unemployment still hasn't budged from its safe range. The Fed is prepared to keep interest rates high until that number rises. That's a bad sign for companies that are running out of cash. They might not be able to refinance their 2025 debt maturities.

Over the next few quarters, we believe more and more companies will struggle to refinance. And that has the potential to set off the next recession.

With that in mind, let's jump into this month's Timetable Investor review...

Checking In on the Timetable Investor

Every month in the Timetable Investor, we use a gauge – like the grades we issue for companies in the Altimeter – to go over the macro market signals. We also highlight how these should influence the construction of your portfolio.

Our advice might not change from month to month, as we're often looking at longer-term macro signals. Always be sure to check back, though, to ensure nothing is different.

Let's get started...

The Timetable Investor for July 2023

This month, all four gauges stayed put. Here's our updated outlook on the current state of the market...

Credit (55% of overall grade) – Credit markets remain tight

Between the 5% rise in corporate borrowing costs... and the first tightening in bank lending standards since early in the pandemic... the credit market has changed for the worse.

While we're not in a freeze, banks are raising lending standards as the Fed is prepared to keep rates high. And the credit market now thinks interest rates and credit risk will rise.

Because of this, we've recently been through one of the fastest borrowing-cost jumps in history. This will make corporations less willing to borrow for investing.

Banks have followed suit. Lending standards have tightened for the last few quarters. They were coming from a fairly open position, but any level of tightening can slow growth.

We've been monitoring lending standards for this type of inflection and will continue to do so. If lending standards keep tightening, it could further stifle growth.

That being said, right now, corporate America still has limited near-term debt maturities. The next credit headwall isn't until 2024... and the next major credit headwall is some time away.

Most companies were able to refinance their debt maturities in 2020 and 2021. That helped defer any issues with headwalls. But corporations and consumers are starting to show signs of stress from the Fed's aggressive rate-hike cycle.

The longer credit remains tight, the higher the risk for companies that can't afford to refinance at higher rates. They'll have to make tough decisions. And that could lead to defaults.

Earnings Growth (30%) – Growth signals are getting weaker

As we've discussed in the past several months, we've been waiting for growth signals to accelerate. The average age of assets remains a key part of the long-term earnings growth story.

Even before the pandemic, corporate management teams were underinvested in their businesses. As a result, the average age of assets on corporate balance sheets continued to fall to historically low levels.

With old assets, corporate production capacity is constrained. That limits the ability to meet demand... even when upstream supply-chain delays from suppliers with similar capacity issues aren't creating problems.

For some time now, it has been clear that management teams will eventually need to invest in their balance sheets to keep operations going. This capital expenditure ("capex") cycle will need to be historically large to return assets to normal operating levels.

This will still be an important driver in the long term. That said, the Federal Reserve has been actively trying to slow growth... and it's doing its job. Corporate earnings growth was negative 3% in 2022. And earnings are forecast to drop 9% this year.

As earnings growth has slowed, so has management teams' willingness to invest. Assets had been getting newer last year. Now, they're getting older again, on average. That means management isn't investing enough to replace old assets.

Plus, commercial and industrial (C&I) loan growth is dipping. Loan growth is strongly related to corporate investment. It's another sign that management is pumping the brakes on growth.

It looks like earnings growth will enter a holding pattern – or possibly slow down – as corporations deal with inflation, high interest rates, and a possible recession. As such, our earnings growth grade remains negative.

Momentum (10%) – Sentiment remains elevated after the market rally

In the midst of the banking mini-crisis in March, it looked like investors had started to pay attention to the various risks in the economy.

As stocks sold off, investors were buying more puts to protect their downside. Equity investors were stockpiling cash, waiting on the sidelines.

But that pessimism didn't last long...

As regulators stepped in to make sure the regional banking system didn't collapse, investors took that as a signal that nothing could sink this market.

Since then, equity investors have jumped back in. Now, equity allocation is at bull market euphoria levels. The equity put/call ratio, a good indicator of panic, has returned to more normal levels.

Investors no longer appear to be focused on risk.

We think that we're in a sideways market for the next several quarters. But this overly bullish sentiment means we're at a higher risk of a pullback in the short term than we have been in a few months.

It looks like we're at the higher end of this range-bound market. Any bad news could send us lower. And the market will likely trade sideways in the coming months.

Valuations (5%) – Valuations are elevated

In the past month, U.S. corporate valuations have stayed high.

Based on Uniform earnings, valuations are at 21.9 times. That's lower than last month's 23.8 times, but still elevated relative to where inflation and interest rates are.

Despite the fact that credit and earnings signals haven't improved, the market keeps rallying. Investors seem overly focused on the tech rally and trends like artificial intelligence, which is why valuations keep rising.

Considering the current inflation and tax environment, a 22 times earnings multiple is too high. Combined with overly bullish investor sentiment, it points to downside for the market in the near term.

We still think this is a range-bound market. Right now, valuations are toward the higher end of that range.

Overall Grade – Negative Market Outlook

The credit market is tightening... But the risk of a serious wave of defaults is mitigated by the lack of near-term debt maturities.

At the same time, earnings growth no longer looks like it could help push the market higher. At this point, it appears growth will be on hold and could even fall slightly.

Valuations have elevated after the market rallied to start the year. Earnings growth has turned to shrinking, and credit availability is limited. Overall, there's not much reason for the market to rise.

And investor sentiment is bullish. That increases the risk of an imminent drop if investors get bad news. We could see more volatility in the next month.

Equity Allocation Outlook: Neutral (five- to 10-year horizon – money should be reallocated to 50% equities and 50% bonds)

Investors should always seek to keep their assets in the right types of investments depending on when they'll need access to cash. Short-term (less than one year) cash demands should always be in cash, not the market.

Cash you might need in two to five years can be in bond funds and other income investments.

Money you won't need to touch for more than 10 years should be entirely in the equity markets. In the past 150-plus years, the U.S. markets have rarely seen a 10-year period where money in a diversified stock portfolio has lost value.

For money between five and 10 years, we'd normally recommend splitting it 50/50 between bond investments and equities. When our data is giving us more bullish signals, we recommend investors get a bit more equity-focused for this money. And when it gives us warning signs, we recommend more of a bond tilt.

We still recommend a neutral 50/50 split. Valuations and sentiment could move in any direction. While we continue to monitor the market, staying neutral is best.

Dollar-Cost Averaging Timeline: 24 months

When deploying new money into the market, jumping in all at once can be dangerous. There are proven investing and psychological benefits to spreading out your purchasing when you add new money to your investments.

In terms of how long you should spread out that investment, it depends... You should weigh the opportunity cost of waiting to buy versus the risk of short-term volatility, which makes any individual entry point a bad one. By weighing the Timetable Investor macro data, we can better figure out that risk-reward setup.

Dollar-cost averaging is just another way to spread out your stock buying over a set period. It involves buying a portion of your total planned investment on a regular schedule, no matter what the stock does.

If you're using six-month dollar-cost averaging, you might buy one-sixth of your target investment each month or one-twelfth every two weeks.

In general, we think the proper range is between three and 24 months, depending on the market.

Last month, we targeted 24 months... the longest in our range. Nothing major changed this month, so we're sticking with that recommendation.

There are limited near-term upside catalysts. And there are ample potential risks. Investors need to be cautious.

That's a big change in the market from the past two years.

Regards,

Rob Spivey

July 27, 2023